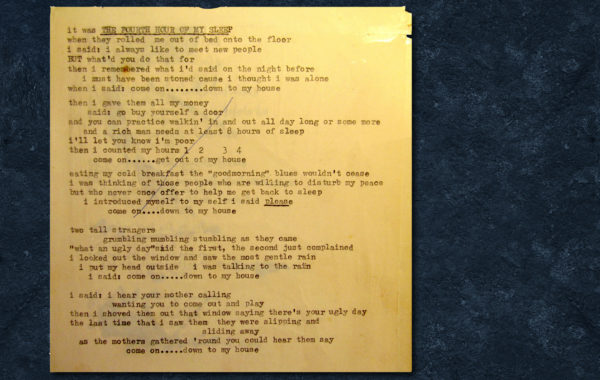

BIOGRAPHY

SHORT BIOGRAPHY

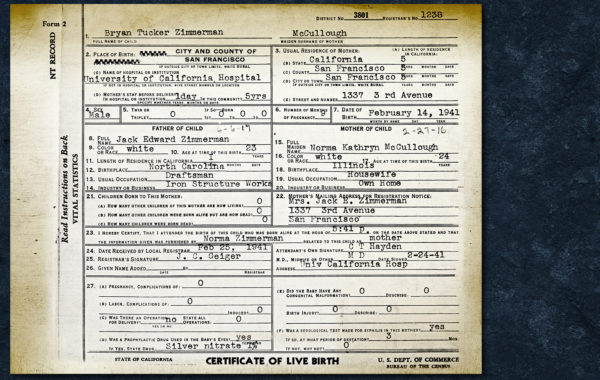

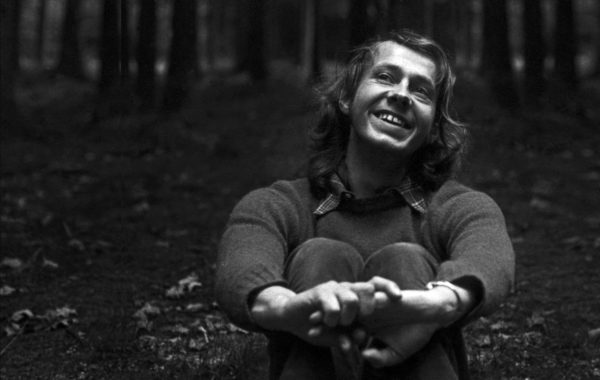

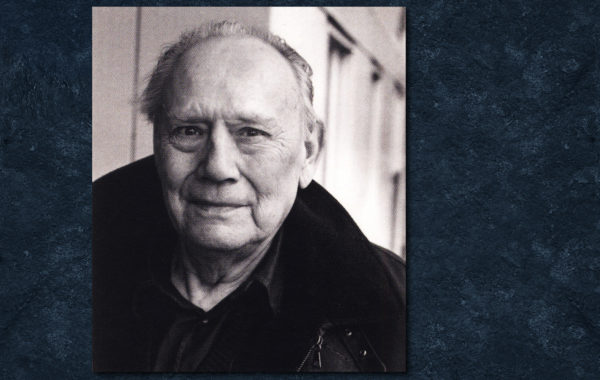

TUCKER ZIMMERMAN was born February 14, 1941, San Francisco California, studied music there from the ages of 4 to 25, and completed his studies at San Francisco State College (now University) in theory and composition in 1966.

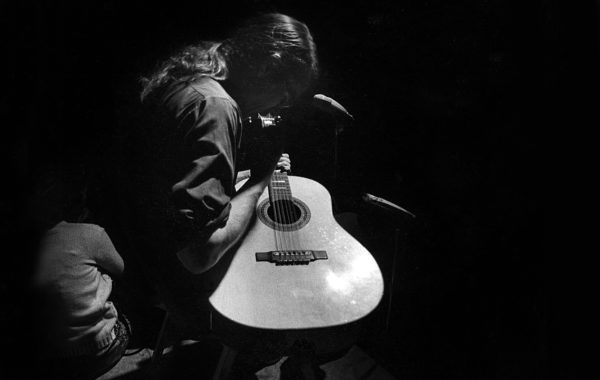

In 1965 he began writing songs (words and music) for his own voice with harmonica and guitar and to date has written over 800 such songs.

In 1966 he received a Fulbright Scholarship to study composition in Rome, Italy with Gofreddo Petrassi. In 1967 the scholarship was renewed for a second year. During this time he began to perform his songs in various folk clubs in Rome.

After a two-year stay in London where he recorded his first album of songs, he returned to the continent and began living in Belgium. From 1970 to 1984 he played hundreds of solo concerts all over Europe, especially in Belgium, Switzerland and Germany where he was regarded as a « song poet ». During this period he also continued to write songs and recorded 5 more LPs. In 1984 he stopped touring as a solo performer. His creative output from then until 1996 was divided into two media: musical composition and the writing of fiction.

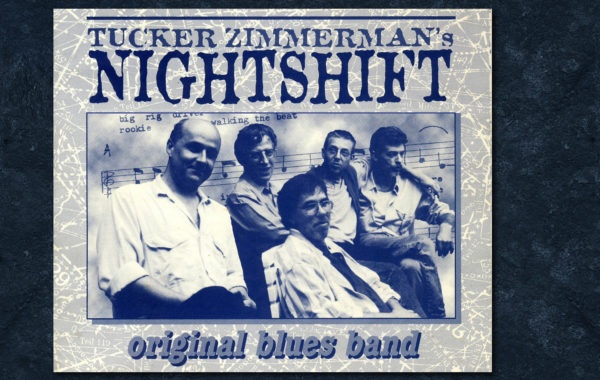

In 1996 he returned to song writing and performing, first with a blues band, and then with his own Nightshift Trio. He continues to be active with his trio. He also continues to write poetry/fiction and to compose music for various acoustic ensembles.

AUTOBIOGRAPHY – CHAPTER I

1.

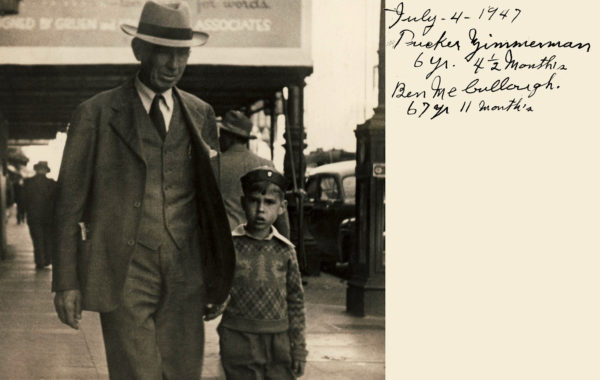

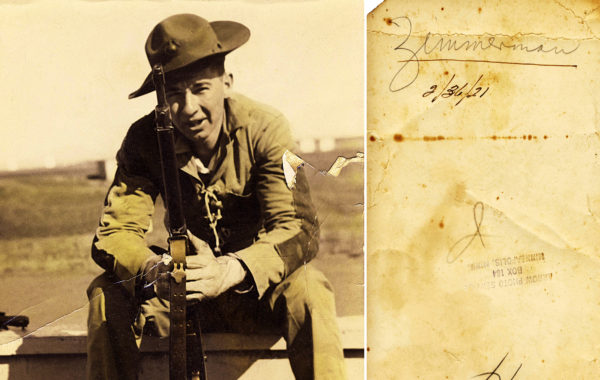

I was born in San Francisco, California at sundown on February 14, 1941 – sun in Aquarius, moon in Libra, Leo rising (for those who might be interested in that sort of thing). My father’s side of the family came from Bavaria in the 1860s and settled in Asheville, North Carolina. My Grandfather, Joseph S. Zimmerman, was an architect and a violin maker. I was told as a child that he designed the state capitol building of North Carolina. I was also given a violin that he made, which I have to this day and upon which I took my first music lessons at the age of four. There is a rumor that his brother was the same Charles F. Zimmerman who invented the autoharp. Another rumor says that Ethel Merman, the singer, was a great aunt of mine and that Harry Zimmerman, the 1940s Hollywood bandleader was a half-uncle. My father’s older brother, Charles Tucker Zimmerman, was an all-American lineman from Wake Forest, but his future as a professional football player came to an end with the start of World War Two when he joined the navy. My dad had already left home at 15 and, lying about his age, joined the Marines when he was 16. He was already married and I was already born when the Japanese bombed Pearl Harbor. He re-enlisted in the Marines and my mother divorced him. I didn’t see him again until I was 24.

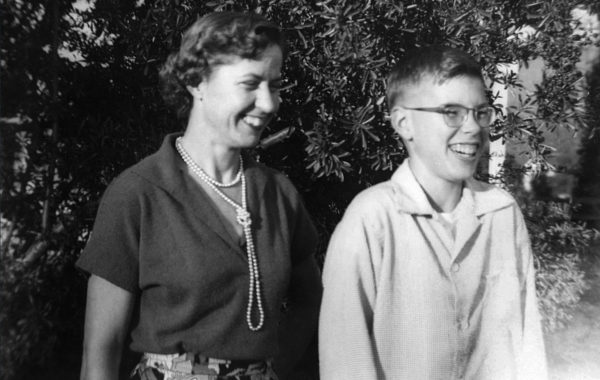

My mother’s side of family came from Scotland way back around the time of the American Revolution. The McCullough clan. I don’t know much about the McCullough clan tho I grew up in their embrace. They came to California during the depression. Grandpa McCullough had been a farmer and my grandmother had been a schoolteacher in Illinois. In San Francisco we lived as an extended family – grandma, grandpa and their three daughters and their husbands and all their children – in a single house on 5th Avenue, just down the hill from the University of California Hospital. I was the first of the cousins to arrive and my father was the first of the husbands to leave. Since the three sisters had day jobs downtown, I was raised by my grandmother. She taught me to read and write when I was four – long before I went to school. We would sit at a blackboard in the kitchen and go thru the alphabet. She would read me stories, then I’d read them back to her. Her favorites were fairytales from Grimm and Hans Christian Andersen. My mind without a doubt would have been permanently warped at an early age by those grotesque tales if her readings had not been balanced by stories from Winnie the Pooh and Uncle Remus. I remember some ferocious earthquakes and I remember the boarded windows and the city-wide blackouts at night during the war. Hushed, fearful whispers that Japanese submarines had been seen cruising around the San Francisco Bay. I also remember the visit of Clarence Dobson, black sheep brother of my Aunt Aline’s husband, Hank. One day when I was about five he appeared at the door with a beat-up steel string guitar and a bottle of whiskey. My grandma quickly sent me upstairs to my room to keep me from being contaminated by this wild creature, tho I later snuck down the stairs when everyone was gathered in the living room to hear him sing his songs. I don’t know whose songs he sang, perhaps some were his own, but I do recall a couple had some pretty rowdy lyrics and at least one was deep on the raunchy side. Late that night I was awakened by a commotion in the upstairs hall. I peeked out my door and saw that Clarence, staggering drunk, babbling like an idiot, had been caught trying to sneak a loose woman into the guest bedroom. From that night on I had two adults I wanted to grow up and be like. Grandma and Uncle Clarence. The puritan and the free-wheeling rascal. The Saint and the Sinner. To this very day I still feel the tug of war these two are playing with my soul.

When I was in the second grade my grandma thought it would be a good idea if I stayed after school for an extra hour each day to take special French lessons. I didn’t learn much – boite, crayon, plume, tableau – and I quit after a few weeks. Not even my grandma could have had the foresight to know that I would eventually spend half of my life in a French-speaking country.

In the third grade I got to see clearly for the first time. Because of alphabetical seating I was stuck in the last seat of the back row. I squinted and tried to copy what the teacher wrote on the blackboard but it was hopeless. Grandma saw the weird squiggles I brought home in my notebook and quickly figured it out. I needed glasses. They tested my eyes. Technically blind in one eye (20/800) and extremely myopic in the other (20/200). With corrective lenses they brought me up to 20/40 in my right eye. It was a revelation. I could see colors. Peoples’ faces. I saw my own face in the mirror for the first time. It wasn’t until 50 years later that I learned the truth about my left eye. The Belgian doctor who tested me for a new pair of glasses said – offhand – that there was not much she could do about the left eye because of the scar. What scar? The one you got when you were born, she said. Had to be forceps birth. The doctors had ripped the retina right in two. What gets me most about this revelation is not that the doctors conspired over the years to cover up their mistake, but that they actually had me running around with an eye patch over my good eye, to strengthen the weak, and when all their work failed as it must – they blamed me for the failure. I wasn’t trying hard enough, they said. It was my fault if I couldn’t see. I believed them. That’s what you do when you’re eight years old.

Also in the third grade I almost beat a kid to death with an iron pipe. He was one of the eighth graders who used to hold me down on the sidewalk outside the gate after school and let a huge German shepherd dog lick my face. I would have probably killed the kid right there in the schoolyard, up against the flagpole, if the teachers hadn’t grabbed me and hauled me away. I was frightened, profoundly shaken by the incident, and I often think back upon it and remind myself that the line between the barbarian and the civilized man with his ten commandments is very thin. The incident got my folk’s attention too. I was already on my way to a life of petty crime. My new glasses made shoplifting very easy. Nickels and dimes, candy bars and comic books. At the age of eight I was hanging out with 12-year old boys and getting anatomy lessons from their sisters. My grandma thought a change of scenery would be beneficial. The Dobsons – Aunt Aline and Uncle Henry – were about to move north to a ranch in Sonoma County anyway and it was agreed that I’d be moving with them. To make it even better grandma would be coming along too. It was also not unlikely that Uncle Clarence would drop in again someday. Maybe I’d get a better look at his guitar. Maybe he’d teach me one of his songs. Or maybe – best of all – he’d tell me a story about one of his wild women. I loathed the city and everything about it, especially school. I welcomed the change.

2.

I don’t know where I’d be today without the life that was waiting for me in Healdsburg. Sometimes I think I’d be at the bottom of a deep dark hole, dead or alive, one or the other, but who knows? I was 8-years old and for the first time the world started to make sense. The kids in the fourth grade made me feel at home, showed me how to fit in, became my friends. One of them – Pete Petersen – has remained a close, life-long buddy. Then there was the forest in back of the ranch. Over the next ten years I hiked the hills all the way to the coast – 30 miles of gentle wilderness – with a hunting knife in my belt and a sleeping bag slung over one shoulder. I spent nights out there. I wandered in the wilderness. I discovered I liked to be alone. I read my first adult novels on these hikes. Zane Grey. John Steinbeck. Jules Verne. Their images are printed vividly forever in my mind and have probably influenced every story, poem and song I’ve written since.

Healdsburg didn’t have a violin teacher in 1949, but I wasn’t too disappointed. I didn’t even think about music for the first couple of months. Then school started and I tried out for the band. I wanted to play trumpet. All the impressive guys played trumpet. I wanted to make a big impression. But the bandmaster – Charlie McCord – took one look at me and said you’re a trombone player. And so I was. I was soon taking private lessons from Charlie and piano lessons from his wife, Florence. One buck each. I remember leaving the dollar bill on the edge of the piano and Florence pretending it wasn’t there. The McCords treated me as a special person. They said I had talent. I disappointed Florence a great deal. The piano really didn’t interest me very much and I seldom practiced. However I got to be quite accomplished on the trombone. Charlie McCord was a retired U.S. Army bandmaster from the Presidio in San Francisco and he tolerated no monkey business. I practiced hard for him and I became his prize student. I gave my first public performance when I was ten. It was a hot, summer night in the town square. The Plaza. This was before television. Everybody came out on Saturday night, sat around on the grass, eating sno-cones and gossiping under the strings of colored lights. I stood up on the bandstand and – with Florence banging away on a piano – I slush-pumped out the melodies of Far Away Places and Jeanie with the Light Brown Hair. The crowd applauded. I was hooked. Thruout my elementary and high school years Band was the only class that held my interest. I got poor grades in every other subject. In my three years of high school I was selected to play in the California Youth Symphony. At graduation Pete gave his valedictorian speech and I played my trombone solo. Some of my classmates – these forty odd years later – still think of me as a trombone player.

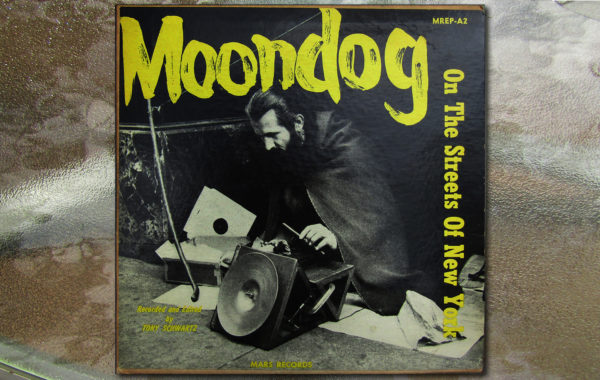

I enjoyed playing the trombone, but the repertoire itself seemed dusty and stale. Stephen Foster tunes were about as good as it got, but they belonged to another generation. I wasn’t desperate tho. My heart was already captured by another kind of music. When I was ten, on one of my infrequent trips down to the city to see my mother, I discovered the musics of Leadbelly and Moondog. Left alone during the day in the flat while my mom was at work, I amused myself by playing thru her record collection. She had a huge collection of Dixieland, some of the old time stuff from New Orleans with the Preservation Hall Jazz Band as well as San Francisco’s Yerba Buena Jazz band with Lu Waters and Turk Murphy. I especially liked the sound of Murphy’s barrelhouse trombone and I would play along with these tunes on the record player, doing my best to imitate every note. For a very short period of my young life my biggest aspiration was to grow up and play in a 5-piece Dixieland band. However, on one particular visit, I put on a couple of records I’d previously over-looked. One was an extended EP, 45 rpm – a live recording of Moondog playing on the streets of New York. The instruments he played were of his own invention – all percussive – with names like Utsu and Trimba. One of his pieces was called Fog on the Hudson. Another was called From One to Nine – “nine quarter beat rhythms in Snake Time.” I loved the idea of music being played in Snake Time. Moondog also recited a few of his poems on this recording, crazy couplets that stood out like neon lights in my brain as cars honked horns in the background. Moondog was a unique and fascinating man, and one of the finest moments in my life came 25 years later (1975) when after a playing a gig in the small German town of Recklinghausen I was invited to Moondog’s house for a visit. We talked for three or four hours, almost till dawn, me sitting cross-legged on his bare floor while he squatted before me, blind, white bearded, clothed in a robe of colorful silk scraps he’d sewn together himself which made him look like a rare tropical bird. He advised me never to forget the importance of counterpoint. But back in 1951, Moondog was merely a distant, eccentric man, playing some very eccentric music on what was to become a very rare recording. I didn’t get him into focus until a few years later when I was in college and started to compose music myself.

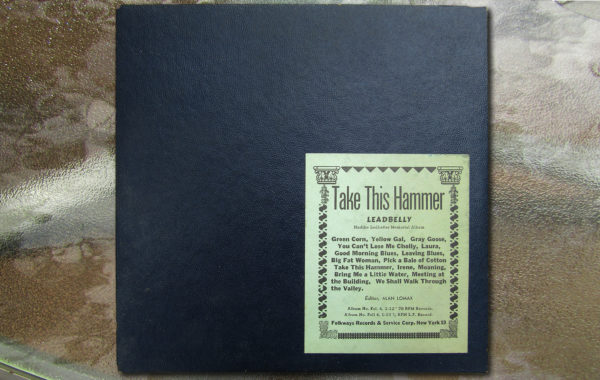

The other recording was a 10-inch long play on Folkways, edited by Alan Lomax for the Library of Congress. There was no picture on the blue-pebbled cover. Just a pasted on label that said TAKE THIS HAMMER: LEADBELLY. On the record were a dozen solo performances. Green Corn, Grey Goose, Good Morning Blues, Goodnight Irene. On one tune he played piano, Big Fat Woman, but on all the others he played a guitar that stopped my heart and made time stand still. His voice was peculiar and high pitched, and I was excited by the idea that a musician could give himself such a crazy name, but his guitar was the most special thing about him. I later learned that it was a 12-string, and from that moment on I vowed that if I should ever play guitar someday it would have to be a 12-string.

Meanwhile, back on the ranch at about the same time (1951), I was busy discovering yet another kind of music. One hot day that summer I was idly pawing thru some junk in the spare room when I came upon an old radio that had been discarded. My grandma’s. She said it was broken. I could have it. I was at a strange period in my life when I enjoyed taking apart complicated pieces of machinery and appliances and never putting them back together. I was getting ready to attack and demolish the radio, in fact I had just removed two of its five vacuum tubes, when I got the idea of sticking them back inside the wooden box in their wrong places. I plugged in the radio again, half hoping that it would explode, but instead found that it had switched on and was in perfect working order. I took it back up to my room and rolled the dial thru a lot of static until I came to a station broadcasting the most amazing music I had ever heard. A piano tune with sax and drums and a voice that rose from the guts and cried out thru a smoky throat. After the tune was over the man on the radio said that was The Fat Man – Fats Domino – and then he played another piano tune from New Orleans by Professor Longhair. Tipatina. The only music I’d heard on the family radio was by crooners, fake jazz swingers, and manufactured schmaltz from Tin Pan Alley. This Fat Man and Professor Longhair were real people singing real music. The next day I rigged up a copper wire from my room on the second floor down to the chicken house. A super antenna. It pulled in the station without a trace of static. It was KWBR down in Oakland and the announcer was Bouncin’ Bill Doubleday. I listened to this station every spare moment I had – from 1951 to 1958 – after school, on lazy summer afternoons, always at night before going to sleep. This music settled deep into my dreams. I heard all the great voices: James Brown, Muddy Waters, B.B. King. Roscoe Gordon, Little Richard, Bo Diddley, John Lee Hooker, Jimmy Reed, Ray Charles. I heard all the great vocal groups. The Penguins, the Five Satins, the Four Deuces, the Medallions, Hank Ballard and the Midnighters. This music stirred my soul, altered my mind, changed my life. I didn’t know what these singers looked like, and in fact it didn’t occur to me until much later that they all had dark skin. All I knew was that they were real people and their music was authentic. It was an honor to be in the presence of their voices. I’m still influenced by these great, sometimes unknown, often neglected artists. At first they called it Race Music. Then they started calling it Rhythm and Blues. I believe that my real musical life began with the magic sounds that came out of that old magic radio. I took these songs to the piano downstairs (when nobody was around) and figured out how to play them. In the Still of the Night, Earth Angel, Bright Lights Big City, Buick 59, Annie Had a Baby. My aunt once caught me playing Bobby Freeman’s Do You Wanna Dance and told me that I would probably go to hell if I continued to sing that kind of music. That comment fueled my rebellion even more and actually for a few moments one day (when nobody was around), I really did sound like Hank Ballard. That moment might have been the height of my musical career.

Rock ‘n roll came storming in a couple of years later and I was knocked out by some of the artists – Jerry Lee Lewis, the Everly Brothers, Danny and the Juniors, Buddy Holly, Richie Valens, but I always came back to the Fat Man on KWBR, back to Huey “Piano” Smith and Professor Longhair. These were the ones I wanted to imitate.

Healdsburg in those years was a great town to grow up in. I even enjoyed going to school. I played in the marching band for football games and parades. I played in the pep band at basketball games. In my senior year I talked three of the guys in the pep band into a rhythm ‘n blues band. I taught them how to play the Fat Man and others. I gave us a name – the Four Casuals – and we went out and played for local dances and weddings. Our big moment came when we won a contest in Santa Rosa and we drove down to Vallejo to tape a single in a real recording studio. I wrote the tune for the A side. Jammin’ the Blues. We did Elevator Operator for the flip side. The engineering technique in that studio was unique. They put each of us in one of the four corners of the room, stuck a mike in the middle and told us to play as loud as we could. I never found out what those two tunes sounded like, but I was proud to be in a band with a record. There was catch tho. All we had to do was come up with a thousand dollars and they’d print up a few copies and take them to the radio stations. Nobody had a thousand dollars, not even my grandma. Just as well. It was scam. And certainly Jammin’ the Blues was not top ten material. Everything else was one big, cosmic joke. At the Italian weddings we got paid in wine – as much as we could drink. One afternoon at the Country Club I got up and danced on the piano – then passed out, crashing down like a sack of potatoes into Tom Johnson’s drum set. That was The Four Casuals last gig.

A week later I packed my essential belongings in Tom Johnson’s Buick station wagon and we drove south to San Francisco where I was about to go to college.

One curious incident on that 75-mile drive still makes me wonder. Among my essential possessions was a guitar I’d found in the spare room at the ranch. A cheap 6-string that might well have come from a Montgomery Ward catalog. I had never played it and I still have no idea why I was bringing it along. That day Tom was burning rubber all the way down Highway 101 and somewhere past Santa Rosa with Little Richard screaming on the radio, he floored it all the way. The needle climbed past 100 mph, the guitar slid out the open back window and shattered into a million pieces on the black top. We saw it all in the rearview mirror. Tom didn’t even slow down. “It’s a goner,” he said. “To the hell with it.” What still makes me wonder is this: if that guitar had survived the trip and I had actually learned to play it in 1958, what kind of songs would I have played? Or would I have started writing my own songs and what kind of songs would they have been? As it turned out, seven years passed by before I picked up another guitar, taught myself to play it and wrote my first song.

3.

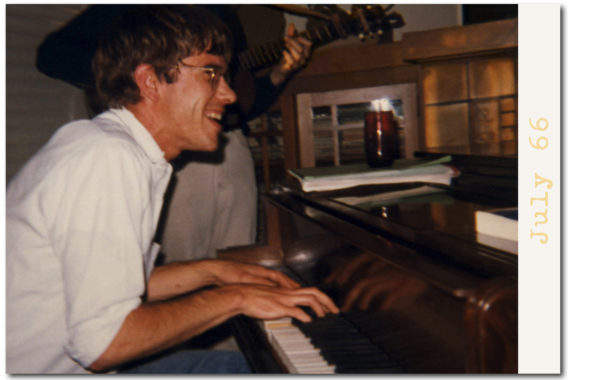

In 1958 the cheap guitar was a small loss. I was a piano man. During the first week in which I was getting settled in the back rooms of my mom’s flat on Second Avenue (Richmond District), I bought my first piano. An old black upright that was almost impossible to keep in tune. $200. It served me well for 8 years tho. My friend Pete used to drive up from Stanford on weekends and we’d sit around smoking, drinking beer and writing blues songs. I still perform one of them. That’s Life – words by P.J. Petersen, music by T. Zimmerman. We were seventeen years old. Pete’s ambition was to become a bum. My ambition was to become a dirty old man.

I loved San Francisco this second time around. It’s just not a kid’s city that’s all. It’s for adults and ageing teenagers who can’t wait to be 21. I had my trombone too. I had a future as a player in some symphony orchestra or as a studio musician down in L.A. I played in a couple of jazz groups. I played in a big band. Count Basie charts. I was lousy at improvisation but I could hit all the high notes and the music was a kick. My life was all mapped out ahead of me.

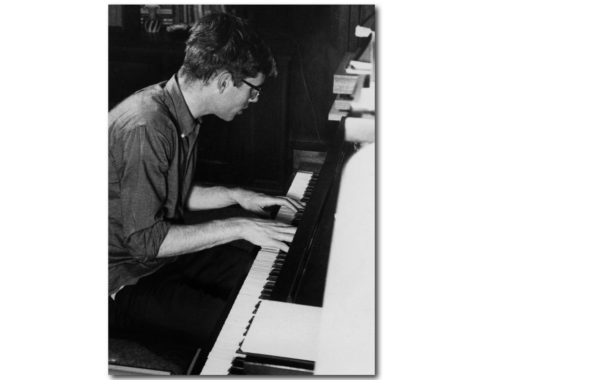

Then I walked into my first theory class with Robert Morton at City College. Within the year I had sold my trombone and I was composing my first piece of music – a Debussy imitation for piano called Le Silence de la Nature (echoes of those after-school French lessons in the second grade) (echoes too of Rimbaud whose opium-addled poetry I was devouring). I studied privately with Morton for two years. Imitative composition. I wrote the first movement of a Mozart piano sonata for him, then a Beethoven Sonata, a Chopin Etude, a Mendelssohn Scherzo, a Schumann Fantasy, a Brahms’s Intermezzo, a Wagner interlude, a Debussy Prelude, and a short piece that might have been part of a Stravinsky ballet. Morton then demonstrated the rules of 12-tone music, gave me a recording of Boulez and Stockhausen and sent me out into the world telling me that I was on my own. He was a great, grouchy teacher. A perfectionist. Very demanding. I owe him so much.

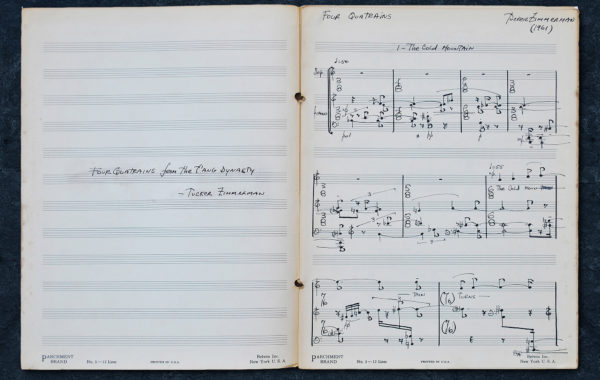

Those first two years back in San Francisco were filled with other amazing wonders. I discovered the poetry of Ginsberg and the prose of Kerouac. I walked in sandals around North Beach on weekends, chain smoking Lucky Strikes, squirting wine into my mouth from a Basque leather flask, looking for Beatniks and hoping maybe that I could become one. I began to write poetry. I read hundreds of books that I never imagined existed when I’d taken those long hikes in the forests behind the ranch. Walt Whitman. Kenneth Patchen. Henry Miller. Thomas Mann’s Doctor Faustus was about a 12-tome composer. I read it over and over. I haunted the City Lights bookshop. I sat in their basement and read Alan Watts and Philp Wylie. I came home with books filled with translations of Japanese Haiku and Chinese quatrains. I read and re-read the essays of Aldous Huxley, C.G. Jung and P.D. Ouspenski. I didn’t understand half of what they said, but I underlined passages anyway, hoping that someday I’d come back and be able to make sense of them all. I memorized entire poems of e.e. cummings and T.S. Eliot. Winnie the Pooh made a come back and Alice in Wonderland also made her re-appearance at this time. These I understood. These still bear their influence. The Jabberwocky is still one of my favorite poems.

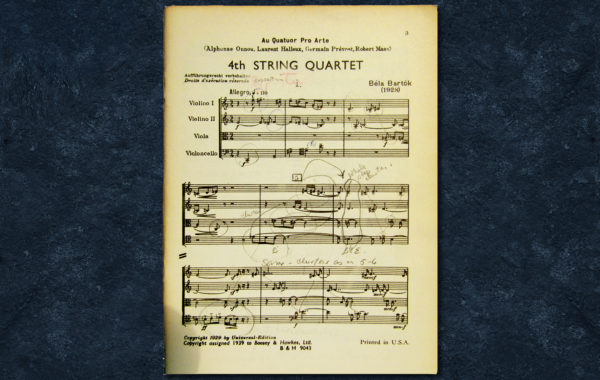

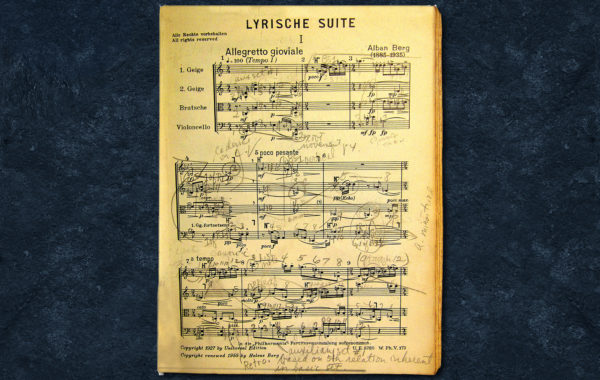

Then there was all that jazz. Horace Silver. Thelonius Monk. Cannonball Adderley. Wes Montgomery. Lambert, Hendrix and Ross, the Modern Jazz Quartet. Still underage, I snuck into the Jazz Workshop on Broadway, hid behind the cigarette machine and let the hard boppers from the east coast fill my head with their chromatic madness. Down at the Blackhawk at Turk and Hyde I caught every set of Cal Tjader, Shelly Manne and other cool cats from the west coast. I was there all three nights, seated at the front table less than 3 feet from the podium when Miles Davis and John Coltrane teamed up to work out the tunes they would later record on Kind of Blue. I talked to some of the musicians, had rewarding conversations with Curtis Fuller (trombone), and John Lewis of the Modern Jazz Quartet. They both spoke of Schoenberg, Webern and Berg. Lewis showed me his analysis of Bartok’s Fifth String Quartet.

4.

Between my first and second years of college, needing a summer job, I signed up with the U.S. Forest Service as a firefighter. They sent me north – to Lassen National Forest, to the ranger station in Fall River Mills. The fire camp – Jellico – was old railroad work camp for the Western Pacific and I shared the bunkhouse with seven other guys. I didn’t have any music with me but I had my poetry. Waiting for fires, I sat on my bunk and wrote page after page of free verse. This soon provoked a hostile reaction from half of the crew, the card players I never joined. They teased me about my poetry. Taunted me. I ignored them. They continued to bait me. The affair boiled over one night when one came over to my bunk and dumped me on the floor. For a few moments I went blind with rage. I was back in the third grade with that iron pipe in my hands. I knew I was in a fight, that we were kicking up a lot of dust, and when I got control of myself less than a minute later I found I had shoved my attacker up against the wall and was pressing my elbow into his windpipe. I was determined to strangle him. It was the frightened look in his eyes that frightened me. I pulled back, puzzled by the extreme violence into which I had plunged. The fight was over tho, and it had a curious outcome. From that night on the fire crew respected me and my poetry. They’d gather around when I’d finish a poem to hear me read it aloud. On a fire, when we’d bump into a crew from another district, they would proudly brag that they had a poet among them, and if any of these other firefighters had suggested that writing poetry was anything less than a man’s job, they would have had to face the seven guys of my crew in a knock-down, drag-out battle. My original attacker, Cap Jacques, became one of my best friends. I saw him down in the city when I went back in school and I saw him again the following summer when I traveled back north for another 3-months with the fire crew.

That second summer with the Forest Service evolved in an unexpected direction. Early in June, the lookout on Soldier Mountain – old Eagle-eye Aaron, had trouble with his eyes and had to come down. The ranger sent me up as a temporary replacement. I stayed. I liked the job. I liked living in a small glass house on top of the world. I liked the solitude. I read a stack of books. I wrote a pile of poems. Every quarter of an hour I’d stroll around the catwalk, my eyes peeled for a sign of smoke in the vast valleys below. I could see east into Nevada, north into Oregon. And always Mt. Lassen stood tall and snow capped to the south. After sundown, while cooking my dinner on the old wood stove, I’d talk with other lookouts on the radio. I liked the job so much that when September rolled around and it was time to go back to school, I asked to be kept on. I stayed on Soldier Mountain until after Thanksgiving that year – and came down to Fall River Mills with the first snow. When the district ranger offered me a full time job, saying he’d make me a fire crew boss the following summer, I decided to drop out of college and spend my life with the Forest Service. And I might have stayed if not for one small revelation that I experienced about three weeks later. I’d been put in charge of a thinning crew. It was my job to walk ahead of the chainsaw gang, to choose the trees to cut down and mark them with a paint gun. I eventually learned that the 200-acre stand of pines we were thinning had already been sold – 25 years in the future – to a private company that manufactured toilet paper. I also learned that most of the fires I had fought in my two summers with the crew – some 60 fires in all – were also stands of timber the Forest Service was protecting for the same private interests. I resigned. I had better things to do than protect America’s future supply of ass wipes. I had music to compose. I had a more meaningful life to pursue.

5.

The fifties slid into the sixties. San Francisco was an exciting place to live for the next five years. There was nothing visible on the surface. The Beats were retired to their homestead land in Big Sur and their adobe huts in Mexico and the Hippie movement, the Counter Culture, the Underground – call it what you will – was merely bobbing around in embryonic form. There was a folk scene in Berkeley. Joan Baez lived just down coast in Carmel. Jerry Garcia played in a jug band. So did Country Joe. John Cage came to town and created joy and confusion. Nothing specifically sensational was in sight, but everyone could feel it. The vibrations. A vital force shifting beneath of surface of the streets. Maybe it was simply the next earthquake preparing its destruction, or maybe some aberration of mind left over from the media-amputated beat scene.

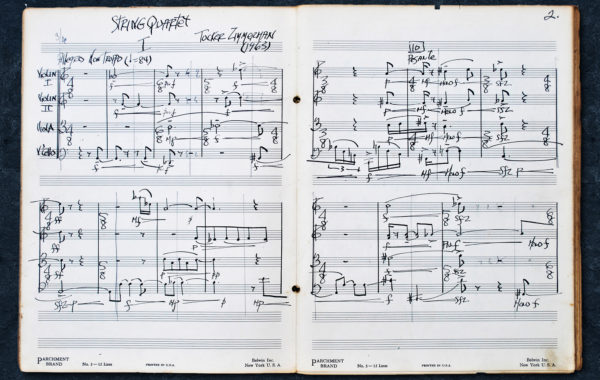

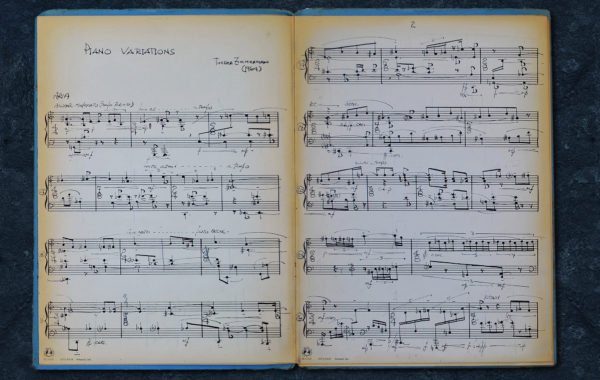

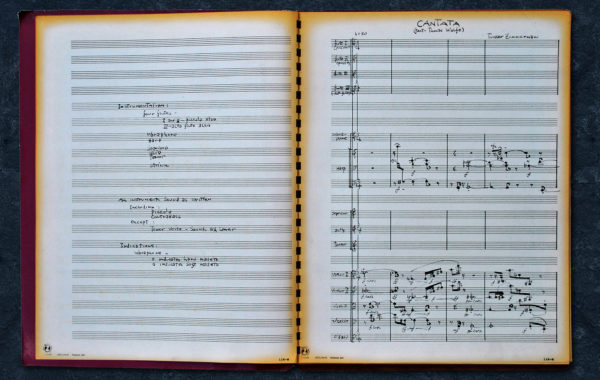

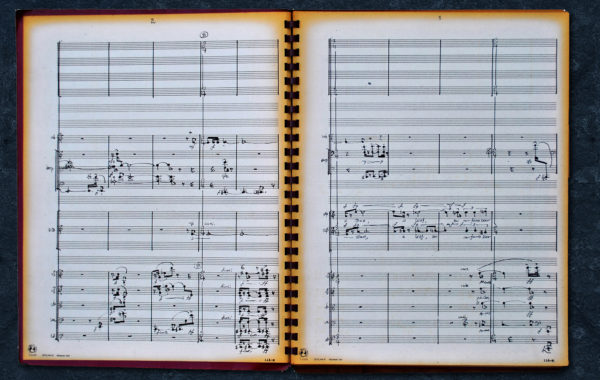

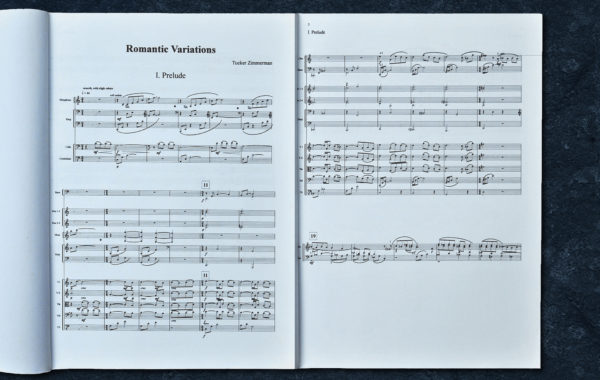

I began to compose my own music. A Cello Sonata. A String Quartet. In 1962 I painted apartments in the Haight-Ashbury at night and later moved into one up on Downey Street. We were all students. It was the cheapest rent in the city. I was now at San Francisco State College studying for a degree in theory and composition and studying privately with Henry Onderdonk. I composed an elaborate set of variations for solo piano. The day JFK was shot, I sat down at my piano and wrote the Aria that would become the theme of these variations. I sat at my piano for the next four months, 14 to 16 hours a day. I forgot about my part-time job as a janitor at Woolworth’s. They phoned up after three weeks and told me I was fired. I couldn’t have cared less. I had better things to do than to sweep floors and stock shelves with crap. I cut classes. Henry understood and covered for me. When the piece was finished he introduced me to Ellen Southard, one of the finest performing musicians I’ve ever met. She played my Piano Variations many times in the years to come up and down the west coast and all the way over to Amsterdam in Holland. I set a few poems by e.e. cummings to music. I composed a Cantata on texts of Thomas Wolfe. Henry guided me thru each piece, showing me what I really was attempting. He taught me how to listen. He opened my mind to a thousand musical nuances I never suspected the existence of, such as the way three flutes sound when playing the same note. I had other excellent teachers at State who gave lessons which have served me well over the years. Wayne Peterson taught me the fundamentals of orchestration and Alex Post taught me discipline in counterpoint (both 16th and 18th century). However Onderdonk’s classes in advanced analysis excited me the most. He introduced me to the work of Luigi Dallapiccola, the Italian serial composer. Later, in 1966, when I expressed an interest to study with Dallapiccola, Henry urged me to apply for a Fulbright scholarship. Henry became a close friend. A mentor. He became the father I never had. He died recently. I loved him very much and I will always miss him.

In 1964 my friend Pete got married. I was the best man at his wedding. I had a few girlfriends at the time but getting married to any of them was the last thing on my mind. One by one I saw friends go down the bridal path and disappear from view. One advised me that the time had come for me to also grow up and put away childish things. Thank God I was smart enough to ignore his advice.

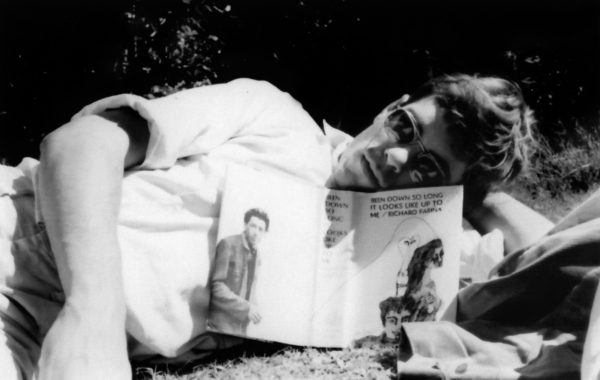

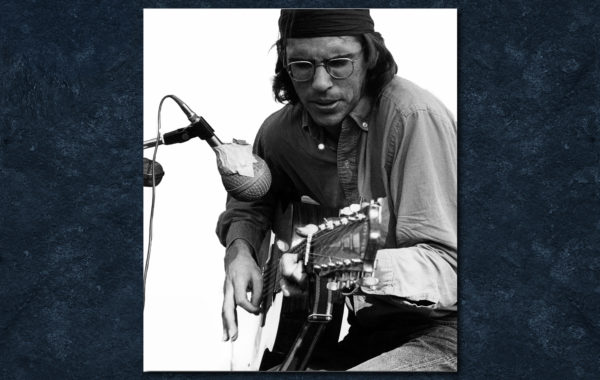

Back in the a scene was beginning to blossom. My friend Don Bailey, who’d been close friends with Richard Farina and Thomas Pynchon at Cornell University, introduced me to some powerful white tablets he’d just received from the Sandoz Labs in Switzerland. The experiences I had were very much like those I’d had when I was eight years old and got my first pair of glasses. For the first time I saw my face in the mirror – only this time there wasn’t any mirror. I learned how very suggestible the human mind is – a valuable lesson for survival in this world of endless propaganda and relentless brainwash. All around me were writers, poets, painters, film makers. We all seemed to be doing the same thing, tho the outward manifestations of our work were different. There was a jug band living down the street. Garcia and the Grateful Dead were living one block over. I got involved in Ann Halprin’s dance group. The Dead were playing almost every weekend at the Avalon. I didn’t miss a set. Things were happening everywhere. I started writing songs. Christmas break 1965, a friend dropped off a brand new Spanish guitar for me to hide. It was a gift from his girlfriend but he was leaving her, moving out, and he didn’t want her to steal back the guitar. It leaned against the end of my piano for a couple of days. On the third night I took it out of its case. Rolled up in the accessory box was a booklet that illustrated how to tune the guitar, followed by pages of diagrams that showed me where to put my fingers to produce the basic chords. I turned my poems into songs. I wrote 12 of them that week. In the following nine months I wrote 45 more. My friend didn’t get his guitar back until I left for Europe in September.

Haight-Ashbury. It all bubbled to the surface at last. Turmoil and confusion. Visions and nightmares. Long hair and beads. Dazed, drug-bombed wanderings and anti-war marches. Pot and acid. Joy and ecstasy. Drop outs and burn outs. We were dancing in the streets. We were leaping out of windows thinking we could fly. We walked around in strange clothes and made even stranger pronouncements. I wrote my first book – a 120-page journal describing the Gypsy-Communal-Hallucinogenic-Pre-Millennial Apocalyptic Earthquake inside my skull. Even today – 35 years later – I cannot decipher that writing. I have no rational idea of what I was trying to express. My songs from this period however are more or less lucid. They still make sense at least. I wrote them all thinking someday a singer would come along and record them. I wrote a few that would have sounded good with the Loving Spoonful. There were a couple that were perfect for The Byrds. In the summer of 1966 I completed my MA at S.F. State and hitchhiked down to L.A. with my guitar. I wanted to sell my songs to a publisher. I ended up singing my first gig in Tarzana – at a clinic for retarded children. There were also some kids there who had incurable diseases and were dying. I knew as I was singing my crazy songs to these kids that this would be the most special performance of life. 40 years later it remains just that. I also met Paul Butterfield that summer. I already knew his girlfriend, later his wife, Kathy Peterson, from the Halprin dance group. I wrote a song for Paul. Droppin’ Out. He later recorded it on The Resurrection of Pigboy Crabshaw album and that was the closest I ever came to having my songwriter dream come true. It wasn’t until many years later, after I’d been on the road singing my songs in Europe, that other artists started to pick them up.

Late in the summer of 1966 I got drafted into the army. At the same time I was awarded a Fulbright scholarship to study composition in Italy. The State Department and Selective Service battled for possession of my soul. At the last moment the draft board relented and let me go, promising me that I would go directly to basic training at Fort Ord the day my scholarship expired and I returned to America. I left for Italy planning never to return. I still have the draft notice among my souvenirs.

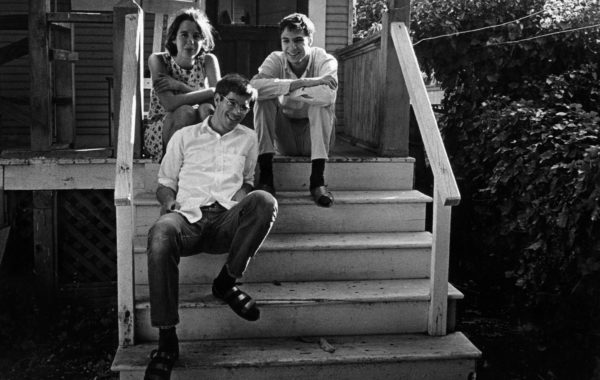

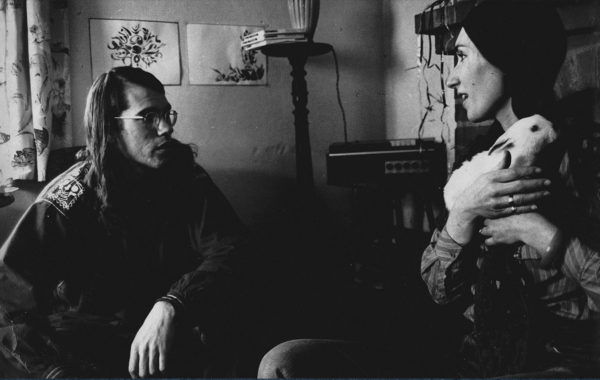

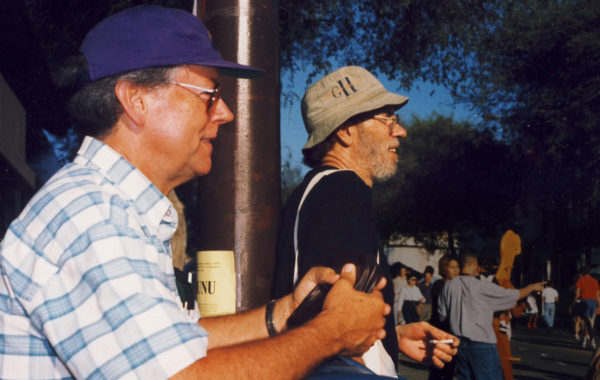

With Zeese Papanikolas and his wife Suzie, back porch on corner of Jackson and Filmore, San Francisco, summer 1966 (photo by Saul Warkov)

6.

Rome, Italy. I was glad to get away from America. California had become much too intense, too chaotic. For the first time in my life I didn’t feel like an alien from another planet. Rome was exciting. Rome was centuries old and it provided me with the perspective I needed. I received looks of respect when I told people that I was a composer.

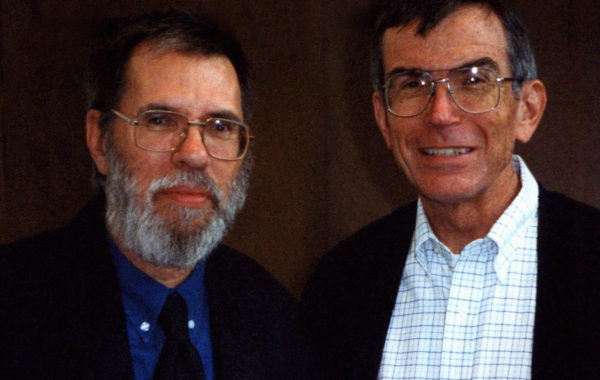

One of the pleasures of my new life in Rome was sharing the excitement of the city with Dan Perlongo, a graduate student from Michigan, the “other” Fulbright composer I had heard so much about in California. Dan and I met on the boat as we crossed the Atlantic and we soon discovered that his teacher (George Wilson) and mine (Henry Onderdonk) were old friends from the days when they had studied with Ross Lee Finney at Ann Arbor. An incredible co-incidence that became more so in that Dan and I became close friends. I saw him almost every day for two years. Often he would drop by the trattoria below my room and we’d share a lunch or an evening meal. Many were the bottles of red wine we drank, many were the miles we walked on narrow, cobblestone streets, and many were the hours of conversation in which we each worked out a lifetime map of ideas and concepts. May every young artist have a friend such as Dan – generous, open-minded, and extremely intelligent. We studied with Gofreddo Petrassi at the Santa Cecilia Academy and shared the often joyful and occasionally painful experiences of being far away from home. A couple of years later Dan returned to Rome on the prestigious Prix de Rome and had the opportunity to spend another year in the eternal city.

In my studies with Petrassi I set words of Dante to music. I put together a tape piece and wrote an orchestral score to go along with it. I was granted a second year on my scholarship. I visited Munich Germany, searching for family. I traveled thru Greece and North Africa. I lived in Florence for a few weeks, another three in Venice. I took a train to Paris, then another to Amsterdam. I’d never felt so much at home. I had a repeating dream – one of my worst nightmares ever: by some mysterious power I had suddenly been dropped back onto a street in San Francisco, I was stuck, without any means of returning to Europe. This dream haunted me for over four years.

Back in Rome, January of 1967, I met Marie-Claire who was then working at the Belgian embassy. We have been together ever since. These 40 years later she is still by my side, guiding me, helping me, sharing tears and laughter.

–

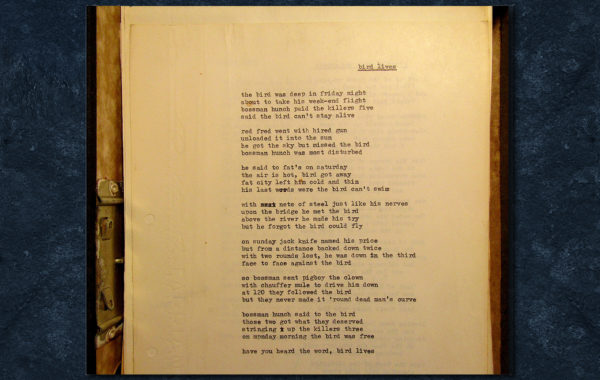

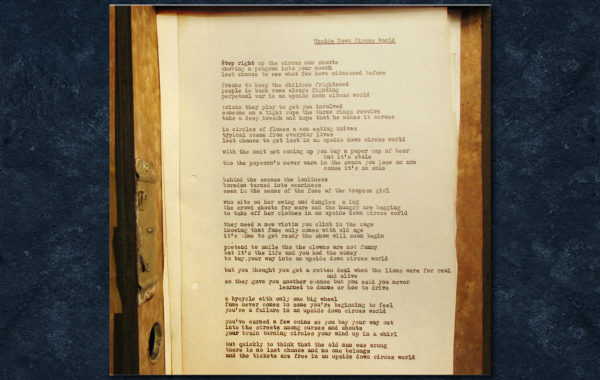

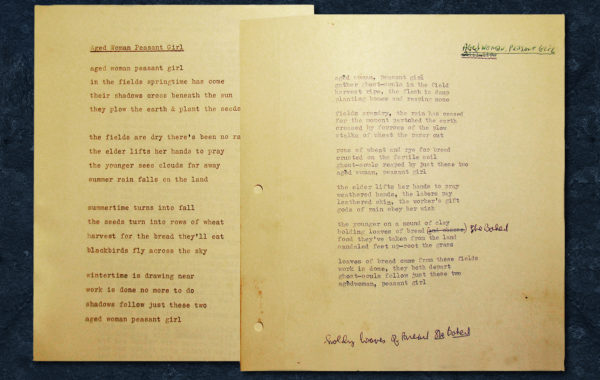

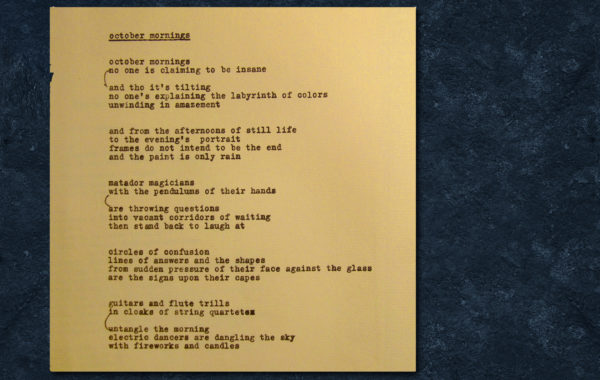

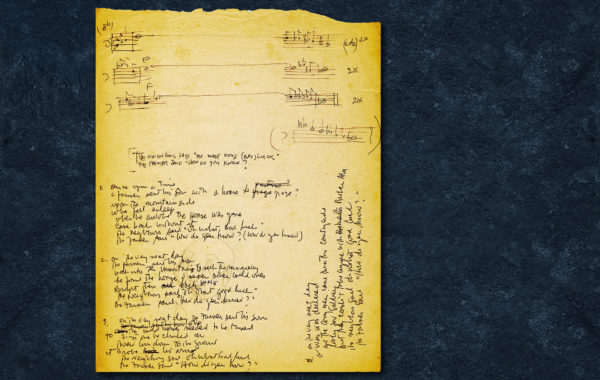

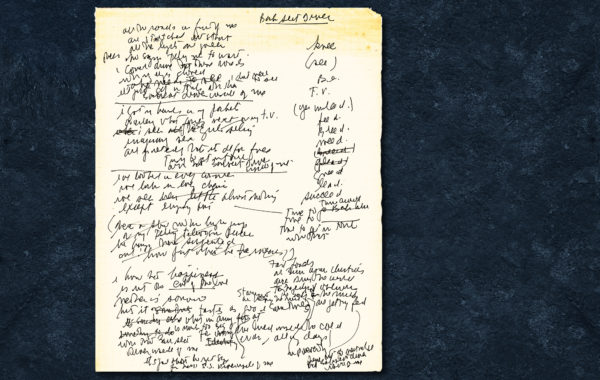

In Rome I wrote over 300 songs. I must say at this point that I have never really been in control of my songs, or have I ever wanted to be. They pop out. They surprise me. They take me to places off the map when I least expect it. I’ve always felt that the songs write me, not the other way around. They tell me where to go, what to say, and how it should sound. I go along for the ride. It’s a collaboration with the muses, if you will. In Rome, my songs took me on some very strange journeys. We traveled thru uncharted lands. Bizarre landscapes.

I met characters who inhabited parallel worlds

Boundaries between fantasy and reality vanished. There were no walls. Structures dissolved.

It was a joyful journey. I’d always been in the grip of a power greater than my own when creating, but this surge of power surpassed all others. Its perfume was intoxicating.

I traveled deep into the distant landscape of these weird songs daily. I went to places where words bumped into each other, exploded, and reformed in new shapes. I played with words and words played with me.

Someone suggested this might be poetry. I didn’t call it anything. I was living in a zone where new languages were being invented every day and forgotten the next. I was too busy getting it all down on paper.

These were not songs that the Loving Spoonful or the Byrds would want to perform or record. They were written for singers yet unborn, perhaps from other planets in other galaxies. It never occurred to me until the final weeks of my second year in Rome that I was writing these songs for myself. For my own voice and guitar. Some of them found their way onto my first album – Blue Goose, October Mornings, The Road Runner. Others I sang once or twice to friends and never again. The melodies to most of them, which I never wrote down, have been forgotten.

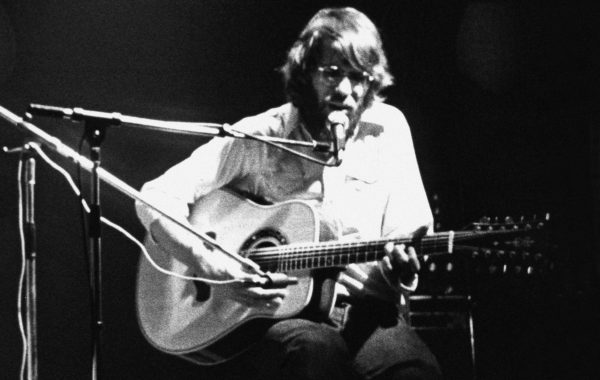

It was in the final months of my second year (May and June of 1968) that I first took my words and music into the folk clubs of Rome. My first real gigs. On my first night I had an audience of one. He sat in the front row, directly in front of me, at the edge of the spotlight. He was wearing a dark suit and sunglasses. He opened a briefcase, took out a comic book and began to read it. He was as strange as any of the characters I’d written into my new songs. I sensed at this moment that the trip that lay ahead of me – down the long road of playing gigs at clubs, concerts and festivals – would either drive me nuts or turn me into some kind of enlightened Buddha.

My next series of gigs were weekends at a club in Trastevere called the Nocciola (The Nutshell) run by an expatriate girl named Janet who’d been on the folk scene in Berkeley a few years before. I had some great nights at the Nocciola. I was treated well. I was received enthusiastically. I even got paid a few thousand lire. That experience encouraged me and confirmed the choice of path I was to follow for the rest of my life.

My scholarship studies were at an end. I’d already given up hope of ever returning to California to finish my PhD. Songs had taken over my life anyway and I decided to ride them to the end of the line. I wasn’t a composer any longer. I was a singer-songwriter. My goal was to find a record company and record an album. I couldn’t return to Los Angeles or New York where most of the albums I listened to and enjoyed were being recorded. It had to be London. My songs would take me to fame and fortune and London would be the first stop.

In late June 1968 Marie Claire and I packed up a rented Peugeot and drove north to Belgium to visit with her family. It was during this week that I bought my first 12-string guitar. I’d been looking for one since I’d arrived in Europe. None were to be found in Rome, Munich, Paris, or Amsterdam. But there in Liege – in a music shop window – stood a $120 Hofner, just waiting for me to buy it. I couldn’t resist. I blew half the money I was saving to give us a start in London. I told myself that I needed a professional instrument if I was going to be a professional recording artist.

On July 4th we packed four suitcases, grabbed my new guitar, jumped on a plane in Brussels and flew to London.

It was the start of another strange odyssey.

7.

In London I soon learned that the U.S. Army no longer wanted me merely as a piece of meat for their war in Vietnam. I was now officially a draft dodger, to be arrested and jailed the moment I crossed an American border. I feared the British Home Office would deport me. I lived for a year and half with this fear. I wanted to record an album. I wanted to play gigs. I couldn’t go to New York or L.A. for the things I wanted. It had to be London. From the very start the British authorities made my life as difficult as possible. The moment I entered the country at Heathrow, customs officials literally ripped the lining out of my suitcases and guitar case and scattered my clothes all over the floor. They didn’t find what they were looking for. I had hair halfway down my back and a beard that flowed to my chest and the officers saw only the image. They either thought I was abysmally stupid, or they were simply getting sadistic kicks by dumping as much grief upon me as they could get away with. They didn’t even apologize for the destruction of my luggage. They allowed me to stay in Britain for 3 months. They refused to issue me a work permit.

Marie Claire and I went underground. Friends fed us and let us sleep on their floors. Friends gave us money. We met many generous people. For a year and a half we lived hand to mouth. The first nine months in London were the hardest. I think I would have given up and gone back to Europe had I not met Tony Visconti. We became close friends. Americans in exile. We were from coasts apart, he from Brooklyn, me from California, but we were joined by a common curiosity for knowledge and a love of music. He produced my first album. He played bass on all the tracks. He got me gigs at which I appeared as a Canadian (Americans needed work permits). He got me jobs as a studio musician playing piano on other artists’ recordings he was producing. The money was all under the table. Royalties from the Butterfield album dribbled in from America. Marie Claire sold her paintings and candles on Bayswater. Living on the street was new to me. Since my first year in college I’d been protected by an academic umbrella. I’d been living on scholarships for the past 8 years. I’d come to London with the erroneous idea that I’d already paid my dues in the world of music. Not true. I had to start over from scratch. Without Tony I would not have survived, much less flourished.

The second nine months in Oxfordshire were a treat, tho we were still living below the poverty line. We rented an old stone cottage on a farm in the hills a few miles east of Oxford. We had a garden that grew spinach. Up the road a huge poultry farm sold cracked eggs for a ha’penny each. We lived on poached eggs, brown rice and spinach. Wind battered our house day and night in the spring. I read books I brought back from Watkins’ in London. Occult books. Nostradamus. Stonehenge. Astrology. I taught myself how to cast a chart. I made a few quid casting other people’s charts then spent it on the Routledge and Kegan Paul edition of The I Ching. We tossed the coins daily, discovering the wisdom of this remarkable oracle. Marie- Claire covered the book in deerskin and it has become over the years our family bible. I re-read all of the Tolkien books. C.S. Lewis’s Narnia stories. the writings of Lewis Carroll – books which had evolved from the landscape I was living in. We were visited by a kind doctor who lived in the next village, Barney Williams. He’d read my interview in the Oxford newspaper and dropped in to see how the Yank was making out. We became close friends. Barney was yet another of the generous souls whose path crossed ours. Many times he brought hot meals to our door. Many times he invited us down to his thatch-roofed cottage for dinner. I fell in love with the English countryside. I took long walks thru its ancient magical forests. Tony brought some friends up from London and we celebrated a memorable midsummer night’s dream. I wrote 150 songs during my stay in England, but I couldn’t get a single artist in London to sing one. My album had come out in December of 1968 – Ten Songs by Tucker Zimmerman – and it was going absolutely nowhere. I learned later that the record company had signed me simply to keep me out of action for three years. They put me in their deep freeze so that I wouldn’t offer any competition to the other (British) singer/songwriters they were promoting. I wasn’t able to record again until 1971 when my contract with them expired.

Things were not turning out as I had hoped when I started this journey back in Rome. The Home Office would never renew my visa for more than 3 months at a time and they kept me waiting in their lines for seven or eight hours hoping I would give up and go away. All my applications for a work permit were denied. I was constantly hassled by the police on the streets of London. Finally in December of 1969 the Home Office called me in and asked to see proof of how I had been supporting myself for the past year and a half. I showed them the royalty statements from the Butterfield song. They said that nobody could live on that amount of money for 18 months. I didn’t argue. They gave Marie-Claire and me a week to pack our bags and get out of England. On Christmas Eve we caught the ferry from Dover and sailed back to Belgium. All in all I was glad to be leaving.

8.

Belgium has become my home. I have now been living here for 37 years. I had no idea when we arrived at the house of Marie-Claire’s parents near Liege that I would staying beyond the end of following month. I was tempted to try my luck and sneak back into the U.S. I still had the voucher from the Fulbright scholarship for one free boat ride back to New York. In fact, I still have it and assume it’s still valid, tho those old passenger liners have long since ceased sailing.

But suddenly other things started happening. Everything that had been denied me in England was being offered to me in Belgium. As an afterthought to the album, Tony and I had recorded a single, The Red Wind/ Moon Dog. It was released in the summer of 1969 and like the album, it was played a few times on the radio then quickly faded back into silence. I was completely unaware that six months later Radio Luxemburg had picked up on the single and was playing it every night, broadcasting it thruout Belgium and France. Tony learned about this a few days before I left England and phoned to ahead to arrange an interview for me in Luxemburg. Marie-Claire and I drove down thru the deep winter snows of the Ardennes and we were warmly received at the radio station. I couldn’t speak a word of French but we made out just fine in English. While we were on the air, I received a phone call asking me if I’d like to play a few gigs in Belgium. The following week I played those gigs – three of them – in Leuven, Mechelen, and Hasselt – and from those nights on events snowballed into an avalanche. So many things happened with such speed in the weeks, then months, that followed that I can no longer recall their order. I did several interviews on Belgian radio with Marc Moulin. The Red Wind/ Moon Dog single was not selling, but Marc kept spinning my Ten Songs and somehow we got a few hundred copies imported from England that we could sell. The Belgian television – RTB – filmed a documentary on me and my music. I played my first real concert in a hall in Brussels – the Theatre 140 managed by Jo Dekmine. 600 kids showed up. When I walked out onto the stage there was only one seat left in the auditorium – the chair behind the microphones. The crowd had overflowed onto the stage and I stepped on a few arms and legs as I picked a path to that empty seat. At last I was in the right place at the right time. I was front-page news in a Brussels newspaper the next morning. I forgot about sneaking back to America. I played dozens of clubs in Flanders, the names of which I’ve long since forgotten – small, warm friendly places. I played for a student strike at the art college in Liege. I made new friends there. None of them spoke English. I sat down with one of my new friends one night and begged him to teach me how to speak French. It took us three hours to get thru two sentences, but I persevered and never looked back. I cannot say that today I speak good French, but my friends understand me and that’s about all that really counts. Most important of all thru these performances I was learning which of the songs I really wanted to sing. That has since become my sole test for keeping a new song: if it stands up before an audience, meaning to say if it resonates with truth within my mind and body when I’m up in front an audience, it will be worth keeping. If a song can survive five nights in a row I know I’ve got one that will be around for a while. I was writing too many songs to worry about five nights in a row tho. My songs became more simple. Easier to understand. When I did a repeat performance at a club in Antwerp a month later I had all new material. In the years to come I never did a gig without performing at least one new song – a song that was entirely new to me as well as the audience. Performing and writing became a single process. I could not imagine doing one without the other. Often my concerts featured only completely new songs. My world of song became like a river. It flowed past my door. I dipped into it for each gig. Songs floated away almost as soon and they floated in. A few stuck.

In 1971 I played my first tour in Germany which included an appearance at the Osnabruck Folk Festival. I’ve never considered myself a folk artist. Those are the boys and girls who sing from a long oral tradition – English, Scottish, Irish – songs they learn as children which were composed by that most famous of men – “anonymous.” My songs were and have always been extremely personal and without any kind of obvious tradition. The most I could ever hope for in the world of folk music is to write a tune that someday singers, perhaps a hundred years from now, would still be singing, my name long forgotten. However thruout the seventies anyone who got up on stage with only an acoustic guitar was classified folk. It didn’t bother me. My music was certainly closer to those true folk artists than it was to the rockers and the poppers. The German audiences, mostly students, were very good to me. They were without doubt the best and most faithful audiences I’ve ever had. We had a very interesting relationship that lasted more than ten years. Thruout the decade I traveled to every city, town and village in Germany it seemed, stayed in every hotel and rode every train. I sang and played to thousands upon thousands of people.

9.

Zaire – now renamed the Congo once again – was as far from Germany and Belgium as I could imagine. My 3-week tour there in the winter of 1970 remains the strangest of all tours. I was part of a package deal that included 4 hard rock bands – two Belgian and two British – bands heavily influenced by Led Zeppelin and Vanilla Fudge. It was my job to open each concert. I sang three or four songs of my choice and then retired to let the bands carry on for the next five or six hours. The most memorable of these dates was the concert we gave for President Mobutu in his private garden – a small amphitheater that was filled with about 200 of his faithful followers. I sat there on the ebony stage, less than 15 feet from the dictator who was ensconced on his velvet throne and clad in his leopard skin cape and pillbox hat and treated him to such visions as The Red Wind, Moondog and Bird Lives. I felt I had looped back in time to Rome – to that first gig at the Folk Club where a man in a black suit and sunglasses had been my only audience. I have no idea how the dictator perceived my presence that night, or what he was thinking. I probably could have been singing in ancient Babylonian and I would have been better understood. But then again, for all I know he was stoned on Congolese and deep in a hypnotic trance the whole time. I finished my three songs, got up and walked off. At that moment Mobutu also got up and walked out. Moments later, his entire entourage followed. The four electric bands played to an empty amphitheater that evening.

I sweated in the jungle for three weeks, slapped gigantic mosquitoes, and danced with children in straw hut villages. There was something about the whole trip that was very familiar. I knew these people. Perhaps I had lived here in a previous life. When we got back to Belgium there was snow on the ground.

10.

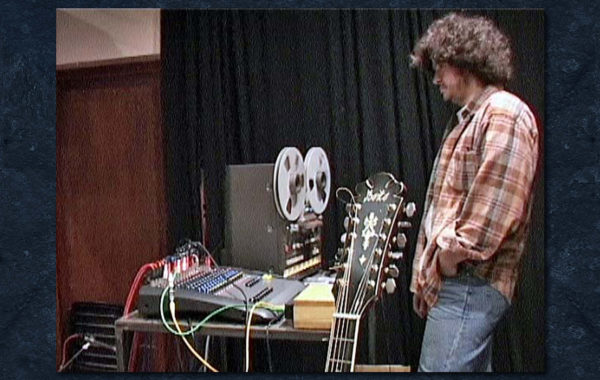

The river of song continued to flow. I dipped into the river and pulled out a few songs and recorded them on a borrowed 2-track tape recorder in our apartment in Liege. These songs were released on a German label, Autogram, in 1971. The album had no title. Just a black cover and my name. Because the tape machine, an old Telefunken, was defective I was able to hear – with headphones clamped over my ears and the volume turned up loud – my guitar and voice which I first recorded on the left side of the tape bleeding over onto the right. Thus I was able to add on the right side a synchronized recording of an organ or an electric piano both of which I borrowed from friends. I adjusted the level of the organ and piano so that the balance would be correct when the tape was played full track mono. Very primitive. We had pillows and blankets stacked over the windows to keep out traffic noises. The album sold a few thousand copies. I met Ian Anderson and Maggie Holland on a tour in Germany. They heard the album, liked it, took the tapes back to England and re-issued it on their Village Thing label.

Many were the friends I made in those early years of the seventies. Jean-Pierre Zaugg the Swiss painter, Manfred Arntz, the German photographer, Jon Gardella, the American sculptor living in Holland, Ton Mass the Dutch translator and journalist, Dany Hermine the Belgian engraver, Didier Bourguignon, the graphic artist, cartoonist and painter. We are all now thirty-five years down the road and are still in close contact. These are my best friends, the ones I enjoy most talking to, being with. It has always struck me as strange that almost all my friends are visual artists, especially since I myself am nearly blind to the visual world. I don’t know how to see. I have absolutely nothing to say when faced with their creations. Yet I’m attracted to their spirit as they are attracted to mine. The greatest compliment I can receive is when one of these friends tells me that he plays one of my tapes over and over again while he’s at work sculpting, painting, drawing, editing film or whatever.

In general I find musicians much less interesting, much more difficult to get along with. We have almost nothing to say, it seems. Few are those I have been able to play with on stage.

There are exceptions of course.

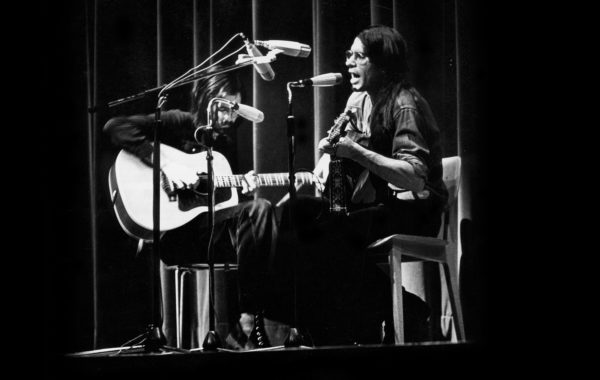

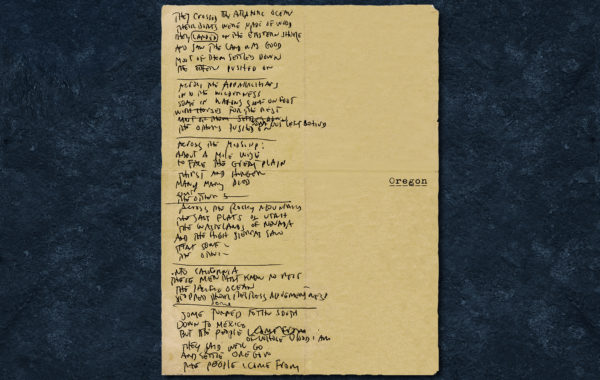

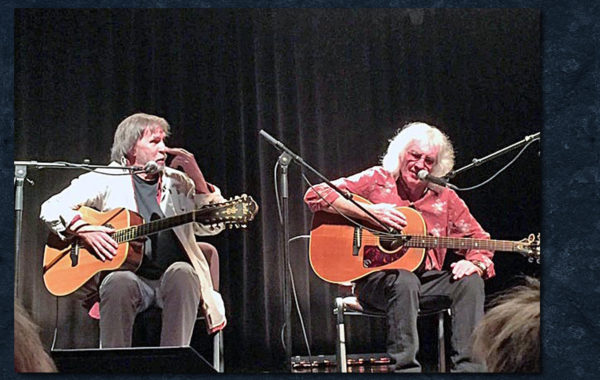

Derroll Adams. It seemed that in every club I played during my first year in Belgium I was told the same thing: Of course you know Derroll Adams. I didn’t, but I soon learned that he was another American, living in Antwerp, and some kind of banjo-picking folk legend. It now seems strange to think about it, but I knew absolutely nothing about Derroll at the time. As a student in San Francisco at one time or another I must have been in a room in which Joan Baez’s recording of Portland Town was playing on a stereo. If so, being not at all sympathetic to the student protest scene, I probably passed it off as just another anti-war song. Hardly Derroll’s fault. Nevertheless – back in Belgium – it wasn’t until a year and a half later, in the summer of 1971, at a festival in Charleroi, that our paths eventually crossed. We became friends immediately. I had the impression that I’d known him for a long, long time. And tho we were to play together several times in concerts and in studios over the next thirty years, we almost never spoke about music. The first time I hitchhiked up to Antwerp to visit Derroll and Danny – about 2 weeks after our meeting in Charleroi – I arrived at a moment when he was busy in his studio, painting. I was quite relieved that he didn’t invite me in and ask me what I thought of his work. I didn’t see any of his paintings until many years later in Kortrijk when about a thousand of his musician friends and fans got together and celebrated his 65th birthday. Nevertheless we enjoyed many long conversations. We spoke mostly of the spirit. He shared his knowledge of the occult and his passion for Chinese and Japanese wisdom. Tho I’d never been a folk fan, he guided me down the path to the heart of his music. I now feel that his songs are among the finest I’ve ever heard. In 1973 I wrote Oregon for him and he honored me by recording it and singing it in performance for the rest of his life. Not only have I written other songs for Derroll over the years, but even after his death in February of 2000 I find myself thinking of him every time I sit down to write. As recently as 2003, returning from the Tonder festival in Denmark, which featured a tribute to Derroll, I wrote another song for him. Turning Point. I could hear his banjo playing the notes of the pentatonic scale. I hear could hear his voice singing the words from the I Ching. I will never go on stage and sing for an audience without thinking of Derroll, without speaking of him, and singing at least one of the songs I wrote for him. This I know.

11.

In the winter of 1971 Marie-Claire and I moved into an old stone house deep in a forested valley in Argenteau, not far from the Dutch southern border. We lived there, peacefully, until 1978. The house itself was some 300 years old and had originally served as a hunting lodge. It was the property of the Baron van Zuylen who lived in his castle up on the hill overlooking the river. In the 19th century the castle had been owned by a countess who used this hunting lodge as a house of assignation for her lovers. One of these lovers was Franz Lizst. Another composer who lived for a few months in our old stone house was Alexander Borodin. I don’t know if Alex was one of the contessa’s lovers or not. Probably not. But I like to imagine that both he and Franz composed some of their greatest music while they were guests in this house. But again, probably not. They most likely went hunting and shot a lot of pheasants. I cannot even pretend that the songs I wrote during these years can be compared to a Lizst tone poem or a Borodin aria, but I did manage to write a couple of solid songs that still survive – Oregon and Taoist Tale. These two are now being sung by many artists in England, Europe and America and are on the edge of becoming true folk songs. Will they outlive Les Preludes and Prince Igor? Probably not.

In 1972 I was invited to appear at the International Poetry Festival in Rotterdam. It was there that I shared a stage with two older poets, Kenneth Koch (U.S.) and Charles Brasch (N.Z.). I was the only one to bring along a guitar. I told the audience: this is the way Homer used to do it. Somebody laughed.

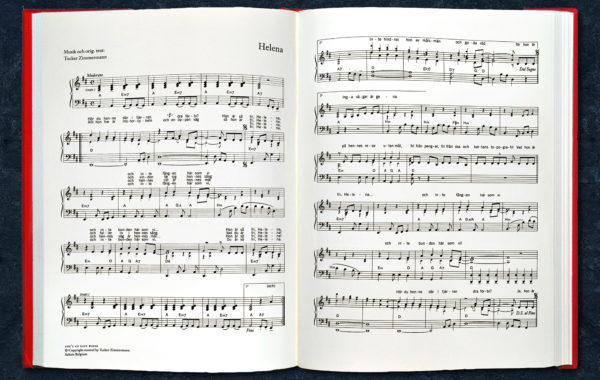

It was during these years that I also had the good fortune to cross paths with Pol Maes, the Flemish painter, Dimitri, the Swiss mime, and Franz Hohler, the Swiss cabaret artist. Several times I visited Franz in his house overlooking Lake Zurich and it was there in 1974 that he and I almost shared a common watery grave. We had rowed across the lake in a very small rowboat and were returning when a storm suddenly blew in. We were far from shore when the waves rose above the sides of the boats and threatened to capsize us, and we were within minutes of sinking to the bottom of the lake and would have surely drowned had not the Coast Guard cruised by, tossed us a rope and towed us to shore. The year before Franz had taken a song from my black album – She’s an Easy Rider – translated it into Swiss-German and recorded it on one of his albums as Es Cheibe Meitli. The same song also attracted the attention of a Swedish translator, Lars Forssell. Later that translation was recorded by a Dutch singer Cornelis Vreeswick in both Dutch and Swedish. Helena he called it.

12.

Many friends visited us in our stone house in the Argenteau valley

Wizz Jones. I’d met Wizz a year or two earlier on one of my German tours. It was in a tent, late at night in Lippstadt. I arrived late – after ten – and Wizz had already played his set. Then, still waiting for me to arrive, he’d gone back on stage to give the restless audience more of his music. I often recall crossing the parking lot toward that tent in the darkness, hearing the pulsing rhythm of his guitar and feeling the emotion of his voice that miraculously escaped the confines of the microphone and the system of electronics that have always burdened live music, and saying to Marie-Claire: who is this man, making this magical music? What does he look like? Later Wizz and I shared a stage in Stuttgart’s Liederhalle and the next day we traveled by train to the Osnabruck festival. We boarded the train, headed for the restaurant car for a cup of coffee, started talking and five hours later – tho it seemed like five minutes – the train was pulling into the Osnabruck station. From then on, Wizz, either alone or with his family, stayed with us in Argenteau whenever he came over to play Belgium and Germany. I didn’t know until recently that he too is a living folk legend, considered by many to be one of the finest guitarists on the English folk scene from the sixties. I knew he was a pretty good guitar player but what I’ve always enjoyed most about him is his fluid sense of rhythm and his dry sense of humor.

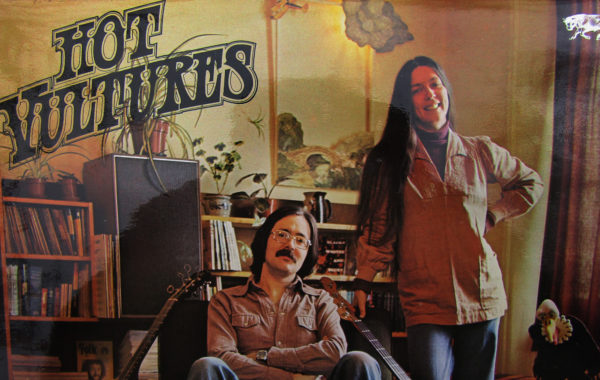

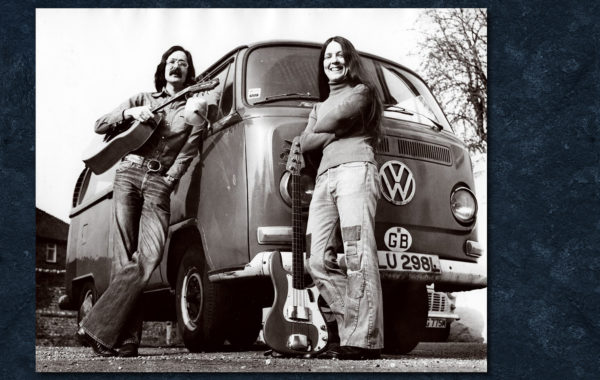

Ian Anderson and Maggie Holland who performed as a duo – Hot Vultures – often made our house their base of operations when they came over from London to play Northern Europe. Many were the nights we sat around the table playing mah jong and talking about science fiction. Because of Ian I ended reading about 300 of those damned novels. It was also during this time that a pair of Americans who had just recorded on Ian’s Village Thing label – Billy Lackey and Kathy Sweeney – drove up to our door in a beat-up orange VW bus, unloaded their guitars and autoharps and stayed for a couple of weeks. Another American singer/songwriter – Chuck Pyle – who had just recorded an album in Holland wandered thru with his country songs and stayed just long enough for us to regret his departure. Billy is now somewhere in California, I hear, Kathy is back in Arizona, I think, and Chuck has long since disappeared into the mountains of Colorado. It was Billy and Kathy who left a note of farewell on our table that said: so good to have friends.

I often think about these three friends not only because we enjoyed so many evenings of music together, but because they also, being Americans, altered my perspective on America. It was during this time that Jimmy Carter pardoned all of us unpatriotic sinners and the door was open for me to return to my home. I knew it was too late, that I would never again consider America anything other than a place to visit, but these three friends did help me come to peace with myself, and for the first time in 8 years I began to have positive thoughts about America. I learned from them that it is erroneous to think of American as a single unit, but rather as several different Americas: political, linguistic, social, geographical, natural. It is a mistake to think they are one and the same. Over the years people often ask me if I get homesick. I have to say that I don’t miss the political or social Americas at all, but I certainly do have a longing for the forests and the mountains. Europe has none of the space that I find in Northern California and Oregon. There is nothing in the world that compares to the force and the music of the Pacific Ocean crashing against the rocks of the west coast. These I miss.

13.

The seventies were by far the most active years of my life. I was touring Germany two and three times a year. I went down to Switzerland for a tour of small theaters about every six months. I played in every corner of Belgium. I played in France, Italy, Hungary, Holland. I did a short tour of England and Wales (with work permit). I recently came across my booking calendars from the seventies and was surprised to note that in one year alone – 1974 – I played something like 230 dates. Most of my gigs in the early 70s were in clubs, but by the end of the decade I was playing almost only concerts. A few festivals too.

In 1974 I traveled to Paris to record my third album. Over Here in Europe. I spent a week of nights in an old hotel on Rue de Prague and my days in an 8-track studio near the Gare de Lyon. Two things excited me about working on this album. One was that the producer, Jean-Paul Barriolade, arranged it so that I could at last get my hands on a synthesizer. They were expensive instruments in those days. Few people could to afford to own one and I was not among the few. This particular one was not a Moog, as I had hoped, but an Arp monophonic with a much softer and mellower tone. It came with the studio. I spent every down-moment of those sessions as well every lunch hour experimenting with the incredible sounds this instrument could produce. I have since come to be disappointed by the way the synthesizer has been developed and manufactured. This is the only true instrument to have been invented in the 20th century and I had always hoped that a new music which corresponded to the large range of unique sounds it offered would evolve alongside its technical perfection. This was not to be. Still today it is conceived of as a substitute for traditional orchestral instruments. The usual synthesizer comes packaged with presets labeled flute, trumpet, harp – and so forth. A new language should have been developed by now. We should be thinking in terms of oscillators, filters and envelopes, we should be viewing the production of sounds from a purely electronic standpoint – as sawtooth waves, sine waves – and so forth. But no – it’s still flutes and trumpets. No imagination. The opportunity to explore the treasure of a new musical domain has been squandered.

The other surprise waiting for me in Paris was the opportunity, at very long last, of getting a chance to work with an Ondes Martenot – one of the first, if not the very first electronic keyboard instruments to be developed. A precursor of the synthesizer, it was invented in the 1930s by Jacques Martenot. I’d first heard the Ondes on an old recording of Olivier Messiaen’s Turangalila Symphony while I was still a student. I immediately wanted to compose a piece for the Ondes – or rather a piece for a quartet of Ondes since they are monophonic (one note at a time) instruments. But nobody in San Francisco knew where I might find one. Soon after I arrived in Rome I came across the score of Jolivet’s Concerto for Ondes. At last I had chance to study the instrument’s technical limits and how it was notated, but again no Ondes were to be found in Rome. Surely, I thought, when I went to London, I would find an Ondes here and I will use it on my first album. Tony was fascinated with the idea but none could be scared up. We learned then that the Ondes existed in only one city in the world. Paris. It was my first demand when Barriolade gave me the chance to make the album. The Ondes we rented was one of only six units in existence and it came with a musician. I was not allowed to play the instrument and definitely forbidden to look inside to see what made it go. Jacques Martenot evidently had a great fear of Japanese spies who would discern his invention’s make-up and operation and would soon be flooding the market with imitations. Martenot refused to mass-produce his instrument. Even with these limits – of being obliged to notate the arrangements on music paper and discuss them with the musician from a distance of ten feet – it was a thrilling experience to multi-track the Ondes and have its shimmering, transparent sounds glowing behind my songs. It blended well with the Arp and I still feel today that in terms of musical sound this is my best album. As an arrangement for The Girl Who Cried My Tears I finally got to compose that Ondes Martenot quartet.

I was pleased with these songs. After years of writing and filling a box with over 500 song sheets I had finally found my path, my originality, my voice. It had become clear to me in the previous year that songs of only one kind were worth spending time on: those which had a positive message and a peaceful vibration. I still feel that these are the only kind of songs worth writing, the only kind of songs that I wish to offer to others either on record or in performance. No anger. No politics. No teaching. Just poetry. Little hums that perhaps might lift us all above our daily worries and fears, little hums that try to make the world a better place to live in.

14.

Gilles Moniquet was still a student at the Brussels Film school (INSAS) when we met in 1975. He asked me compose music for two short films he was making. I had already scored music for a couple of films before I met Gilles, but it was he who taught me the essentials of the craft. From him I learned that it was not necessarily the images on the screen that needed to be treated musically but rather the intentions of the film maker himself. This was a blessing to me because, as I have already mentioned, I am not very talented with my eyes. My collaborations with Gilles were very rewarding and more than once he told me he loved my music. Sadly he died in a car crash in Paris shortly after moving there in 1976 to begin his first feature-length film. I am sure, had he lived longer, he would have created many beautiful films and I would have written some beautiful music for these beautiful films. Other collaborations with film makers thru the years have confirmed the lessons I learned from Gilles. It is always the film maker himself for whom I write the music, not his film.

In 1975 I began work on my fourth album, using the same method I have always used and will continue to use in the future for my song recordings: the sound of the album is determined by whatever materials I have on hand. What I had on hand for Foot Tap was the stone-floor room in which Franz and Alex composed their greatest works, but which was now my humble studio. I also had on hand a new Revox 2-track recorder, a Shure microphone, a very unprofessional Sansui spring reverb unit that had a beautiful rainbow display of colored lights on the front and a simple 4-channel mixer. Also on hand were a variety of musician friends who dropped by during the next 12 months and added their various talents to the various tunes. One feature of the Revox B77 was that the sounds recorded onto the left side of the tape could be transferred (with a short delay) to the right side at which time I could add another instrument or voice. With the mixer and my friends on hand I was able to build up single tracks of two or three instruments or voices at a time. On some tunes I bounced the tracks four and five times. The final result was half-track mono, but that was no deprivation. I’ve never been a big fan of stereo anyway. The most curious tune on this album is Howling at the Moon. When Jaap Beusekom, the Dutch banjo player, stopped by for a couple of days, I had only the chords and structure of the song. No lyrics, no title, not even an idea of what the song might be about. But I liked the sound of Jaap’s banjo so much that I was ready to put anything that he played on the album. He played thru these chords changes I had worked out against my guitar and we made a recording of it. Two or three months later, after listening to this banjo and guitar duet almost daily, I joined it up with an idea of a werewolf I had been carrying around in my head for the past couple of years. The two fit together, I wrote the words and over-dubbed the voice. People are always asking me how I write my songs. That’s one way.

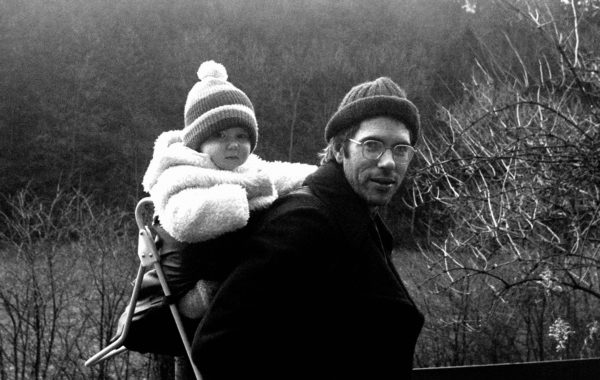

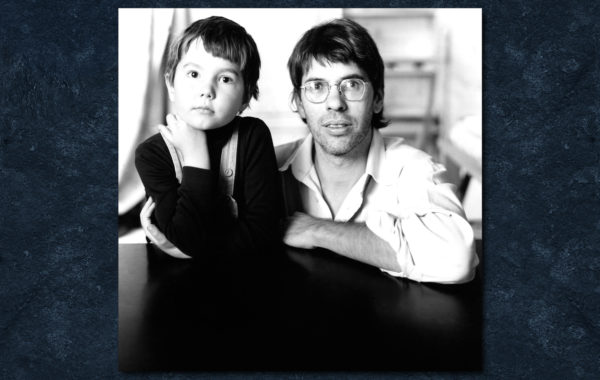

15.

Names. They’re much more than accidental collections of alphabetical letters, much more than convenient labels. They’re sounds, vibrations – some harmonious, some discordant. They have power. They determine how we see the world and how the world sees us (which may or may not be the same thing). As a child I felt burdened by my name. It seemed to be cumbersome. At first I couldn’t pronounce it myself. Too many Ms. In elementary school mean-minded kids had fun with my first name, crossing the T on my lunch sacks and giving me a thousand red faces. First summer in the forest service I was introduced to the fire crew as Bryan – my true first name – which was printed on the work sheet when I arrived. I didn’t bother correcting the error and for the next three months I was a “Bryan.” It was an interesting experiment, but I didn’t feel like a Bryan and I was glad to get back to San Francisco, back into the familiar vibrations of my middle name. In 1974 when the managers of Philips Records in Paris heard the tapes of my Over Here in Europe album, they wanted to release it on their label – on one condition: that I change my name. I said I’d agree if the record company would change theirs. At the age of 33 I was way beyond the showbiz triviality of a name change, and I certainly was conscious of the importance of names when my son was born two years later. I wanted to get it right. Tho born in Belgium he was automatically eligible for American citizenship and I wanted him to have a true American name. The previous year I had read a shelf full of books about the American Indians and I was well aware that these were the only people with true American names. One of the most outstanding figures in these histories was Quanah Parker. I admired him from the first. An amazing man. In his lifetime he guided his tribe from a stone age world into the modern era without pausing to experience the industrial or the electronic revolutions. In the late 19th century he was the last of the Comanche war chiefs. His was among the very last of all the tribes on the continent to surrender to the white man. Then, after recovering from an illness which took him to a shaman in Mexico, he returned to his tribe in Oklahoma with the gift of peyote and became a leader of the Native American Church – the visionary religion that uses peyote in its ceremonies. From war to peace in one generation. From the first moment I encountered his name I felt the beneficial power it contained. In the Comanche language Quanah means Eagle. And that is how our son, born on an Indian summer day in October of 1976 became Quanah McCullough Zimmerman.

16.